The Power of Place: TV Worlds That Feel Alive

How geography and setting drive storyworlds

Like many kids, I loved Walt Disney World growing up. I was lucky enough to visit many times as a child, a luxury I know my parents saved for and loved just as much as my brother and me. If you’re familiar with the Disney theme parks, you know that there’s a particular feeling you get just past the entrance at any given park. Every one of your senses is activated: you might see a castle, you smell popcorn, you hear music, you can already taste the Mickey ice cream bar (or insert your favorite snack here) you’re going to enjoy later and you can feel the ground under your feet change. That last one is important: topography is part of the Disney theme park magic.

I remember watching a documentary or special about the construction of Disneyland and other parks many years ago. You might not actively notice it, but when you walk from the entrance of the park and Main Street, U.S.A to Adventureland, the ground underneath your feet shifts. Main Street has a paved street and trolley car grooves, but transitions to a rugged brownish terrain with animal paw prints and moss stains as you veer left toward a new land, making you feel like you’re in a jungle setting. Compare that to Liberty Square where you’ll find colonial-era bricks and stones, or Tomorrowland, where the ground is smoothly paved and concrete gray. Worldbuilding quite literally starts at your feet here. You know what kinds of stories might take place given the ground beneath you. Setting and topography determine your experience.

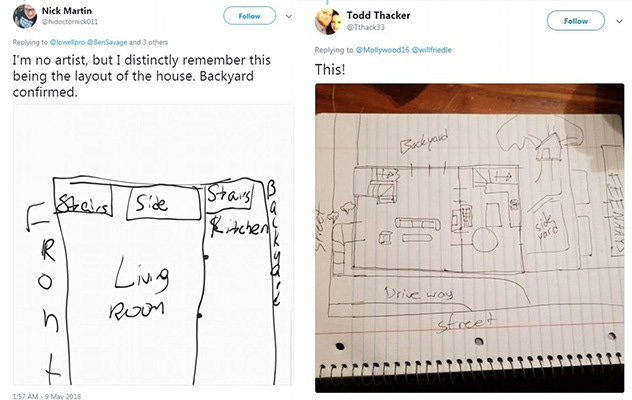

In the sitcoms I’ve loved my whole life–those with a studio audience like Friends, Full House, Boy Meets World–the settings are somewhat still. They are backgrounds. Much was made of the Full House set, how the actual interiors of the home we saw on screen couldn’t possibly match the structural layout of the real Victorian townhomes seen in the opening credits and establishing shots. Pod Meets World hosts Danielle Fishel, Rider Strong and Will Friedle consistently argue about the backyard/side-yard mysterious topography of the Matthews residence on Boy Meets World.

It’s clear that this sitcom doesn’t truly consider place as a character. You could probably pick up the entire show, place it in a different city, and notice very little difference. (In case you forgot: the show took place in Philadelphia. Was that apparent? No.)

But settings on shows like LOST and Gilmore Girls have more agency. The setting shapes behavior, controls possibility, and determines who the characters are allowed to become. The land doesn’t just hold the story; it steers it. Just like in a Disney theme park, the topography, geography, and decisive sense of place steers the story and guides a guest’s experience. It’s similar when watching a TV show where the setting has been well-crafted, and steers how the story is told.

Setting as Antagonist

One of my favorite shows, LOST, has a knack for bringing viewers into the setting in a visceral way. There are moments on the beach, with all its beauty and glory of waves crashing, sunsets, and beautiful soft sand. Something about that setting signals that the scene is going to be safe: maybe a tender moment or important talk would happen there. Compare that to when the survivors enter into the jungle, where one crack of a branch could send your blood pressure through the roof as a viewer.

On both the beach and in the jungle, the human characters are isolated from the rest of the world and even each other as viewers learn about other inhabitants on the island. This isolation removes societal rules the characters are accustomed to in the world they left behind. New social structures form: leadership emerges, conflict bubbles up and is dealt with by the group, and survival is often a question of how well they function together as a community. The island seems to choose who survives, which brings the free will of the characters, and their decisions, into new light. As they discover the secrets of the island, like the hatch, or secret dwellings, these findings test the survivors. The topography of the island seems to determine these folks’ fate–not the other way around.

Geography as Emotional Containment

In Gilmore Girls, the fictional Stars Hollow–famously filmed on the WB studio backlot–is a social ecosystem. The town feels real because in essence, it is. You can visit the lot and walk around and see Luke’s, Miss Patty’s, Kim’s Antiques, Lorelai and Sookie’s house, and Doose’s Market easily–even if the lot is dressed for another show or movie shoot.

I can name several other shows off the top of my head that have filmed on the same lot and the feeling of those shows share a similar DNA. The walkable nature of the town is explicit on the show; often the characters stroll from home to home or from home to the market, diner, or school. The town has traditions that play out in the square around the gazebo, and everything feels incredibly safe, even nostalgic. It’s when the characters leave this walkable safety net that events feel a little more high risk: Lorelai feeling stressed at dinners at the Gilmore mansion in Hartford, Rory going to Chilton and encountering high pressures and expectations as well as culture shock with other students, attending college at Yale and meeting new people who grew up in the kind of environment her mother tried to shield her from. In this show, geography protects or exposes the characters: Stars Hollow is a warm blanket, maybe even slightly stifling for growth, while points outside of the town offer new, challenging situations to contend with.

Geography as a Wound

In Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Sunnydale is sitting directly on a Hellmouth. In Stranger Things, Hawkins sits on the Upside Down. A layered landscape where something dark lies beneath the suburban normalcy that the characters inhabit adds drama and storytelling potential. In the case of Buffy, an entire series could play out over seven seasons and one hundred and forty-four episodes; so many creatures and evil beings could lurk around that town because of the Hellmouth.

An underworld of some kind in any setting provides endless opportunities for story building. And furthermore, a suburban idyllic landscape above breeds secrecy, long-term scars, and comradery amongst those who can see it versus those who cannot. The place itself carries memory and trauma, and all inhabitants can feel it. This is best illustrated when Buffy receives the Class Protector award at Prom, or when Jason interrupts a town meeting to pontificate about the strange happenings around Hawkins in Stranger Things (he gets it pretty wrong, but he at least sees that something is absolutely amiss in town).

Geography as a Pressure Cooker

I love stories set in a contained environment, like a college campus or a boarding school. The sense that the characters are largely confined to one place creates a pressure situation where tensions might bubble over at any minute. It’s why The Real World was a huge success decades ago. We love live-in-a-house-together shows like Jersey Shore and Summer House, romantic game shows like The Bachelor or Love Island, and psychological competition shows like Big Brother and Survivor.

The show Tell Me Lies, based on Carola Lovering’s novel of the same name, follows a group of college friends whose toxic relationships at school come back to haunt them later in life. In the world of college, freshman Lucy meets new friends on the first day and sheds her old identity from home. She meets Stephen, an older boy with dangerous vibes (and a girlfriend, not that it seems to matter to him). In this limited physical world, Lucy can’t escape Stephen even if she wanted to, and the neverending loop of classes, dorm room visits, and campus parties puts all of the characters in close proximity all the time. Every character is trapped in toxic cycles of keeping secrets, and being retraumatized by one another’s misdeeds. When they leave college, will they all heal? The show relies on flash forwards to a later date, years after graduation at a wedding for two of the friends, and viewers can see that even though they physically left college, those wounds are still gaping. The pressure cooker of college extends to their relationships years ahead.

Geography as Dreamscape

Some settings are comforting and dreamlike, which is perfect for a narrative that relies on nostalgia. The Wonder Years has a bit of a home movie vibe to it; the opening credits were actually shot as home movies with actors looking at the camera as their characters. The voiceover narration in every episode speaks of idyllic suburban memories: a quiet street, kids riding their bikes until sunset, first kisses in the nearby woods. I loved Dawson’s Creek for a similar reason: the coastal town of Capeside was shown as a small town with intimate waterways that powered the community. The downtown waterfront and the personal docks at characters’ homes looked out onto a serene waterscape that felt like a vacation from the real world. In fact, one day I looked up the town they filmed in–Wilmington, North Carolina–and found myself requesting a physical copy of the free tourist guide! I just wanted to see pictures of the real place. I thought if I could see actual photos from their own tourist bureau I could mentally transport myself there. And on a Southern-Atlantic road trip with my mom in my thirties, I finally got to see the entire town in real life, waterways and all. It did not disappoint.

Water imagery often helps characters manage transition. When we meet Joey and Dawson for the first time, she’s climbing out his window to get to her little boat at the end of his dock to paddle home instead of staying the night. Spoiler alert: she ends up sleeping in his bed beside him anyway, despite their very adult conversation about getting older and how they probably should stop having such sleepovers because of, well, puberty. The creek is the body of water that separates their houses but it’s also a metaphor: it’s a boundary between their friendship and possible romantic entanglement; between childhood and adulthood. In the pilot episode, they choose not to cross those boundaries, and stay kids for a little while longer. But in the first episode of Season 2, the two go on a date. And Dawson picks Joey up at her home in a big, shiny speedboat, completing the metaphor: they jump into a relationship–and adulthood–with power and speed.

The landscape of a sleepy coastal town or a suburban block you grew up riding your bike on feels like a transitionary place. It’s small and intimate, but almost begs its inhabitants to long for bigger environments. Stories that take place here are about the in-between: adolescence as a time where decisions feel huge but might not be as earth-shattering as they feel at the time. And looking back on them, we can remember with a bit of wistful longing of a simpler time.

Next time you’re watching a show or movie, take note of the setting. What is it telling you about the plot and characters? I’d love to hear some of your favorites in the comments!

Want more? Our Discord is where you’ll find everything you need to know about our ecosystem at Remarkist! Don’t forget to follow us on Instagram, tumblr, and Spotify for more insights on fandom—and hit that subscribe button so you never miss a thing at rmrk*st Mag!

Really interesting and well written piece! Can we also talk about how the second floor of the Gilmore house has one room?!