Found Family and Traditional Family: What TV Shows Teach Us About Society

Fiction as a model for the real world

Do you remember the first time you saw a TV show or movie that felt like it was FOR you? I do. I have a vivid memory of being six years old, sitting on a loveseat in a small room of the house where my parents had set up a portable TV. (The idea of a smaller TV that you could cart from room to room used to be a novel thing, long before everyone had a video screen in their pockets.) My mom turned on a sitcom, not that I could name it at the time. I really hadn’t seen anything like it before. The show was Full House, and I watched with wonder as Stephanie Tanner, a little girl about my age, got into some hijinks in her family’s living room. Her family was her whole world, and I understood that what happened inside that house between the characters was what mattered most. There were rules and hierarchy, the children having less freedom than the adults–even when some of the adults in this world weren’t parents.

Full House became my favorite show on TV, one I watched religiously every week from that evening at six years old until the very last episode when I was a young teen. The show reinvented the idea of family: while most of the inhabitants of the “full house” were related, the family relied on close friends to become part of their family dynamic. What started out as a premise where single dad Danny invites his brother-in-law and best friend to live with him and his daughters for extra childcare turned into many seasons that consistently redefined the very idea of what a family is and could be. Fiction is an opportunity to build new societies through chosen bonds versus just the ones characters are born into.

Family as the First Society We’re Born Into

Some of the earliest sitcoms of the 1950s like I Love Lucy, Leave it to Beaver, Father Knows Best and The Honeymooners focused on family as the central societal construct. Everyone had a place, and the storytelling centered around family dynamics. This is a prevailing framework; sitcoms and dramas still often center around one family.

When a nuclear family is the focus of a show, the stories all take place within the family dynamics. Narratives between parents and children, siblings, or the central romantic couple dominate. The family has their own rules, values and idiosyncrasies that drive plot. It is a social system in which belonging is inherited, and most of the time, a given. The Brady Bunch is a great example of inherited belonging: in a blended family, the conflict occurs when everyone is included, but bump heads when their individual family idiosyncrasies combine.

In family dramas like This is Us and Parenthood, inherited belonging spans multiple generations, and the central conflicts come from generational habits, lessons, and trauma. This is Us tells a story about a family with three siblings, triplets who lost one biological brother but gained an adoptive one born on the same day. This peculiar but heartwarming premise sets up endless plot points that have the characters questioning their roles both as siblings and sons and daughter to their parents who made a life-altering choice in a moment of grief. Their inherited sense of belonging–or struggles with it–follow them into adulthood.

Choosing Belonging Instead of Inheriting It

Families are mini-societies where belonging shouldn’t have to be earned. But there are many beloved shows we can look to that are set up around a different kind of family: one of found relationships that function like a family especially if the characters’ families are largely out of the picture due to living in different cities.

The first show that comes to mind is Friends, the smash hit long-running sitcom of the 90s centered on an ensemble cast of, well, six friends. I’d be remiss not to mention its predecessor, Living Single, as well. Both of these shows are about coming of age as adults after leaving the home characters grew up in, looking for belonging in a new city and environment. Living with roommates and peers instead of siblings and parents, on their own for the first time, the stories are focused on finding one’s place in the real world.

On Friends, Ross and Monica are siblings, so their family dynamic plays out in their circle of friends. But without their parents around, their antics are less acceptable to others–or, played for laughs. Their childhood family competitions, like playing touch football on Thanksgiving for the Gellar Cup, or their infamous dance “routine” they show off on “Dick Clark’s New Year’s Rockin Eve” seem completely reasonable to them but are just strange inside the society of their chosen family.

Nevertheless, the characters on Friends and other similar ensemble shows like How I Met Your Mother, Happy Endings or The Big Bang Theory live inside a specific kind of society where belonging isn’t guaranteed. The interpersonal relationships between the characters are deep, but could change at any moment and often serve as conflict opportunities. On Happy Endings, the pilot episode begins with one member of the group leaving another at the altar. As viewers meet this ensemble, their future as a found family is already in jeopardy. The success of the series relies on how well the two characters can keep their breakup from breaking up the group entirely, and puts the pressure on the group to stay friends as a unity despite this major, awkward rift.

Man on the Inside, a show about one man’s undercover detective operation inside a retirement home, showcases another type of found family. While the home’s inhabitants are not related, they’ve all chosen to live out their golden years with others in a mini-community living together. Some have suffered losses of spouses, others have families that come and visit. Like shows about young people out on their own for the first time, these characters are on their own again, struggling to find belonging at a stage of life where they’ve had many experiences that inform their personalities but more or less want the same things: love, friendship, and to find purpose.

Workplace Shows: Found Family as a Model for Community

Shows set in the workplace offer a different kind of “found family,” one that the characters aren’t choosing, but are more or less stuck with. The Office, Parks & Recreation, 30 Rock and Abbott Elementary are brilliant ensemble shows where every character has their own unique flair they bring to the group. A sense of belonging is guaranteed because everyone has to come to work every day and are more or less at the mercy of the same set of rules. In any community, this is the case: folks are thrown together randomly and have to somehow make it work–even if they don’t share the same values.

The stories emerge through these clashes: Dwight Schrute on The Office (hilariously) clashes with Jim Halpert almost daily, given that he takes himself very seriously and Jim doesn’t take Dwight seriously at all. Leslie Knope on Parks & Recreation has to inspire her coworkers to believe in the same community projects she does in order to get them accomplished, often with lots of red tape and community disengagement to contend with.

While individual friendships form within these systems, much like any larger community or society, these shows–along with hourlong procedural dramas like High Potential, Grey’s Anatomy, or Law & Order– demonstrate how important it is to find ways to problem solve with others you might not agree with, since everyone is essentially on the same team.

Found Family Is A Powerful Worldbuilding and Storytelling Tool

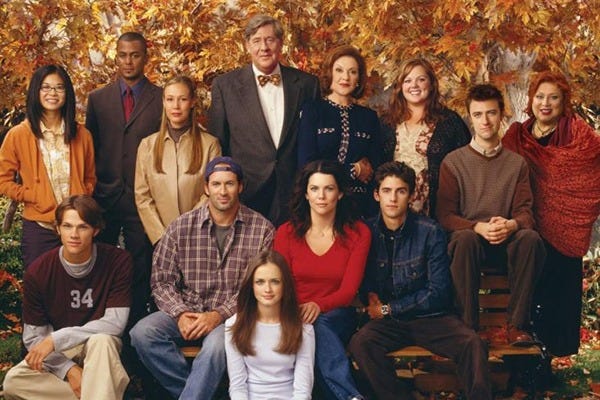

A personal favorite example of a “found family” show is Gilmore Girls. One of the reasons I find the content so rich is that it’s a show about belonging that blends choosing family with inherited family dynamics. Lorelai Gilmore flees her own family as a teenager with daughter Rory to Stars Hollow, a place where she finds a quirky kaleidoscope of characters that offer her the family that she always dreamed of. As Rory grows up, she also inherits the love of townies that embrace the two as if they’ve always lived there.

But the show is also about generational family dynamics, and the central premise sets up a weekly obligatory dinner with the elder Gilmores in exchange for funding Rory’s prep school education. Through seven seasons (and beyond), Lorelai and Rory both individually balance the found family acceptance they discovered in a town they made their own while navigating their place in their own family dynamics. The world of the show is subsequently expansive, the stories playing out both in the colorful, kinetic world of Stars Hollow and the stiffer, monochrome world of the Gilmores from their mansion in Hartford to Rory’s experiences at Chilton and Yale. As the audience sees these characters in two different worlds, we watch as they pursue acceptance and belonging in very different ways.

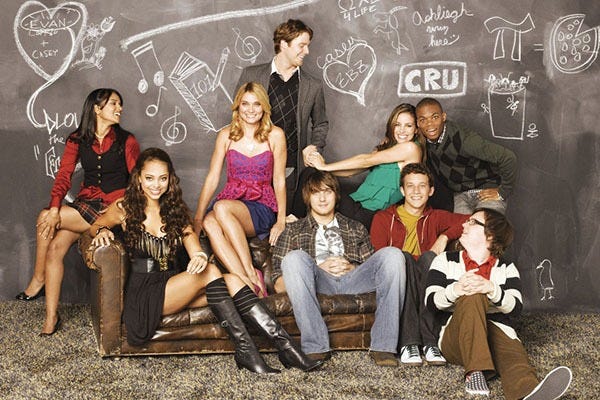

Greek is another favorite show of mine, centered on a fictional college and their Greek life system. While the two main characters are brother and sister, their experiences within their respective sororities and fraternities are as wildly different as they are similar. Themes of found sisterhood and brotherhood drive the plot–even when those relationships can be toxic. Casey struggles with her two love interests, former friends from competing fraternities with very different personalities who are now sworn enemies. Her younger brother Rusty finds himself the only academic scholar in his disorganized, wild fraternity and becomes best friends with a member of their rival frat. The idiosyncrasies of each organization, the coalitions that exist within them, and the forbidden friendships and relationships that exist outside of them offer endless points of conflict and resolution, as well as many different kinds of activities on campus to serve as fertile ground for these stories.

When “found family” on screen is used as a worldbuilding tool, it mirrors how individuals might eventually leave their nuclear family “society” in pursuit of building society in the outside world. A part of me is still six years old, watching Stephanie Tanner get up to some trouble in her living room, my family under the same roof in the next room. Eventually, I’d move out of the house (Stephanie never really did!), and gain perspective watching TV shows where individuals find and build societies elsewhere. Like myself, I’ve watched characters struggle for belonging when it isn’t guaranteed. Watching individuals choose found family in those spaces serves as a model for viewers living out our own stories in the real world. And while family and the family home will always be a fertile ground for storytelling, “found family” stories help us relate to one another in real life, and develop conflict resolution, affection, and find learning opportunities with others who have had different upbringings than ourselves. Which might be the best thing for society as a whole.

Want more? Our Discord is where you’ll find everything you need to know about our ecosystem at Remarkist! Don’t forget to follow us on Instagram, tumblr, and Spotify for more insights on fandom—and hit that subscribe button so you never miss a thing at rmrk*st Mag!