Adventures Through the Past: Inspiring Stories in Historical Fiction

Discover truths of the past through creative stories

In the early 2010s, it was hard to escape the words Downton Abbey; it seemed everyone in the U.S. had become absolutely infatuated with the British television show, created by Julian Fellowes, that depicted the upstairs/downstairs aristocratic life of the fictional Crawley family and their servants. Set in a Yorkshire country estate over the period of time from 1912 through 1926, the series showcases how people in society lived according to their stations. Throughout each season, the family is impacted by actual historical events: the sinking of the Titanic, the Great War, Spanish flu, the Irish War of Independence, and more. Yes, viewers like me were drawn to the drama, but I’d be lying if I said I didn’t sit in front of my television with my phone in hand, ready to google any real event brought up and learn a bit more about it.

Historical fiction is a compelling way to learn about events of the past through people we care about, even if they are fictional characters. History can feel sterile; names in a textbook feel far away and unrelateable. But when we are asked to connect with people of the past (real or not) and provided sets, costumes, and situations, it is easier to put ourselves in the shoes of someone who lived in another time. Here are some of the movies, TV series, and stage shows that made me want to learn more about a historical event or figure, sending me down rabbit holes to learn more.

Apollo 13

In the summer of 1995, you couldn’t escape the massive blockbuster hit movie that was Apollo 13. I was a young teen who had little interest in science, much less the science of space travel. But it was THE biggest movie at the time, so I went to see it on a summer day with my family. I left the theater absolutely riveted, and thinking a lot about the lives of past and present astronauts. I can confidently say that a great deal of the plot points went over my head. The main details I left with were 1) space travel is really dangerous and just about everything can go wrong 2) the 60s were a very cute time for ladies’ fashion and 3) I suppose putting a man on the moon isn’t…easy?

In the early days of the 2020 pandemic, I began listening to a podcast I’d discovered about the fateful mission, called Saving Apollo 13. The podcast goes in depth about the Apollo 13 mission, how it failed, and just how impossible it was to return the astronauts to Earth. So many people, using their own unique skills and knowledge, came together to problem-solve. From the podcast, the details around building a carbon dioxide scrubber for the lunar module, as well as how the brightest minds at NASA figured out how to get the module on a new course home, were more fascinating than I remembered from the movie. But the movie had provided such a great foundation for me: each detail that was revealed in the podcast made me envision the scene the film illustrated for me. Connecting those dots made me feel like I’d really learned something.

A significant change from reality to the movie was the line “Houston, we have a problem.” It was a misquote, used on film for dramatic effect. In reality, after the unexpected explosion, astronaut Jim Lovell maintained a calm tone and said, “Okay, Houston, we’ve had a problem here.” Further research taught me that Lovell’s calm demeanor would characterize the rest of the flight. And while the line in the movie is worthy of a heart-pounding trailer, the film itself does a stellar job of telling the story about the bright minds who left their egos at the door to save the lives of their colleagues.

Titanic

If I was hooked by a movie like Apollo 13 in 1995, I had no idea what hit me in 1997 when the most defining film of my teen years graced the silver screen: Titanic. This movie had everything: the introduction of the stunning Kate Winslet to pop culture, a generation’s obsession with Leonardo DiCaprio, the massive amounts of behind-the-scenes footage from director James Cameron and of course, the Celine Dion song that still haunts us. This film not only made me aware of the “ship of dreams” and the tragic historical event, but my obsession with the sinking of the Titanic was my entire personality for a while.

I heard a review at the time about how the movie was essentially a love story with a massive historical event going on in the background. What a great way to sum up historical fiction: we become invested in the characters and see how a true event impacts them. Through that experience, we better understand the event itself. I was fascinated by the Titanic: I imagined what the news might have been like for anyone living during that time, and I obsessed over the clothes, dishes, chandeliers, and art at the bottom of the ocean. It was possibly the first time in my life that I thought about the potential failure of bold technology, just a couple of years before I’d be anxious about the worldwide fear surrounding Y2K.

Since then, any time there’s news surrounding the Titanic wreckage in any way, I admit my ears still perk up. And I often think about a central idea that the Titanic film introduced to me at a young age: in every generation, there are many times when it seems that progress, greed, and safety are on a dangerous collision course (pun intended), and we might learn from the mistakes of past innovators and risk-takers. Jack and Rose might not have been real (unless you’re swayed by Titaníque the musical), but their story combined with a big budget blockbuster brought awareness to a massive disaster that many young people wouldn’t know about otherwise.

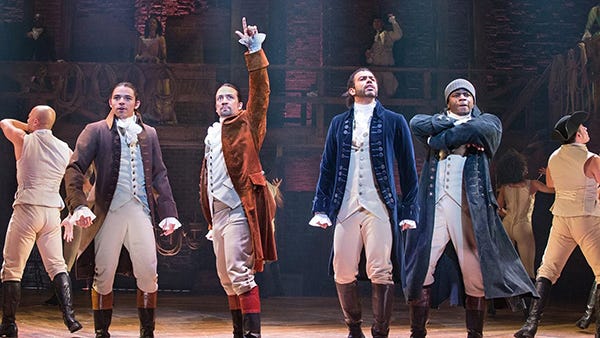

Hamilton

When I watched the filmed stage production of Hamilton for the first time, it struck me with dread how little I knew about the American Revolution and everything that came directly after it. But along with everyone else who could not stop raving about Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Tony Award and Pulitzer Prize-winning musical, I was suddenly alive with interest about the United States’ founding fathers, and the women who loved them. The illuminating production breathes life into facts and events I remembered breezing by in elementary school social studies but never fully grasped: Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, Rochambeau and the Battle of Yorktown, the Constitutional Convention, the Federalist Papers. But I’d never heard of the less famous founding fathers (i.e. the ones whose photos are not printed on U.S. currency), like John Laurens.

Laurens was an essential aide to George Washington, and he was an advocate for abolition of slaves. The musical characterizes him this way, but my history books did not profile this historical figure who, had he lived past the war, might have had enormous influence on the state of slavery at the conclusion of the American Revolution. More research into Laurens begs the question, would his face be printed on some of our currency if he wasn’t killed in the last days of the war? What influence would he have had on the Constitution had he joined the Constitutional Convention with his former comrades?

While some events of the musical never happened (there is no record of Alexander Hamilton having any sort of ongoing flirtation with his sister-in-law Angelica Schuyler, for one), encasing the events of the founding of a nation in modern music is exciting. Using elements of hip-hop, R&B, pop music, and direct references to modern artists as well as musicals of the past, the show connects audiences with historical events in a way they might never have seen them before. Furthermore, the original cast was mostly non-white, providing a satirical message that while the U.S. was founded on principles of freedom, those freedoms did not exist for everyone.

The Gilded Age

After the conclusion of Downton Abbey, Julian Fellowes turned his attention to an American story. The Gilded Age is a sweeping historical drama that blends both fictional and historically accurate figures and events during the so-called era of American wealth and progress which spanned from the 1870s through the 1890s. The show is set in the specific year of 1883 (there’s a reason!), and follows two New York City families: the new money Russells and the old money van Rhijn-Brooks. The show charts real events of the time, including westward expansion of railroads, the early days of the Red Cross, Thomas Edison’s electric lights, and the biggest plot point: the construction of the Metropolitan Opera House.

The first few episodes weren’t exceptionally exciting for me, but I kept watching because I became addicted to viewing with my smartphone in hand. I constantly looked up people, addresses, and events as they were mentioned, searching for photographs and family trees. It was a mental obstacle course, stumbling over facts and fiction. I already knew a great deal about the Academy of Music, the original “old money” opera house in New York City, from my own research during college (two of my dormitories were on the same block as the original site). During the Gilded Age, as people achieved more fortune due to industry rather than inherited wealth, a social gap was formed between those who had “old money” versus those who earned “new money.” The wealth was extraordinary on both sides, but those in the “old money” camp found the others uncouth. Incidentally, I had picked this term up in my teens, watching Titanic, as Rose’s mother and her snooty friends hated Molly Brown because she was “new money.”

In the series, Bertha Russell (played by Carrie Coon) is insulted that she cannot buy a box at the Academy. She isn’t gaining favor with Mrs. Astor, who curates New York’s high society through an exclusive list called the Four Hundred. The show only refers to her as Mrs. Astor, but my casual internet searching identified her as Caroline Schermerhorn Astor, a descendant of the powerful and wealthy Schermerhorns and the Van Cortlandts. While the Russells are fictional, they represent very real people. Bertha is based on Alva Vanderbilt, wife of railroad tycoon William Kissam Vanderbilt. The Vanderbilts’ wealth was so vast that while Mrs. Astor kept them out of society for a while for their nouveau riche flagrancy, eventually she had to acquiesce or risk her own social standing. Alva was instrumental in raising funds for a new opera house, the Metropolitan, which was founded in 1883, the year the events of the show began. Though it moved locations from 39th Street in Manhattan to Lincoln Center in the 1960s, it is one of the most famous opera houses in the world.

Suffs

Alva Vanderbilt makes a distinctive cameo in Suffs, a musical with book and lyrics by Shaina Taub (which earned her two Tony Awards). Suffs is the story of the influential women who organized and fought for the passing of the 19th Amendment to the Constitution, which granted women the right to vote in the United States. Unlike Hamilton, this American history musical features characters based on real change-makers that most people have never heard of–yet significantly influenced their modern lives. While Suffs is compelling on its own as a great story, it sent me deep into research, learning more about the events that led to American women’s legal right to vote in 1920.

The musical references some familiar names I’d learned about: Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Ida B. Wells. But I was shocked that I’d never heard of Alice Paul, the agitator who led the final fight for women’s suffrage and co-wrote the Equal Rights Amendment. In Suffs, we meet Alice in 1913 at a meeting of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) where she confronts suffragist Carrie Chapman Catt for not doing enough to advance the cause. Some more research revealed that Catt had been working in the movement for decades, leading a state-by-state approach. Alice Paul, in contrast, wanted to push the federal government for a constitutional amendment.

As depicted in the musical, Paul put together a younger coalition to organize the first ever Woman Suffrage Procession in Washington, D.C., a successful protest featuring thousands of suffragists from state delegations. Socialite Inez Milholland strode down Pennsylvania Avenue on horseback wearing a crown and a cape, and later became the face of the movement, giving speeches all over the country. In the musical, she collapses to her death after saying the words, “Mr. President: how long must women wait for liberty?” It’s a perfect dramatic moment, and not far from fact: many accounts of the time claim this was exactly what she said before collapsing, returning to deliver the rest of her speech from a chair. She died weeks later from anemia.

These names are recorded for history by one major source: a book entitled Jailed for Freedom, by suffragist Doris Stevens. Stevens is a character in the show, and her book is the primary source for the musical itself. In addition to the internal struggles within the movement between Catt’s NAWSA and Paul’s National Woman’s Party (NWP), it also illustrates the tension between Black suffragists. The characters of Ida B. Wells and Mary Church Terrell, based on real figures, disagree about how to combat racism within the movement.

One of my favorite pieces of history from the show is the introduction of Alva Belmont, who co-founded the NWP with Paul in 1916 by funding it. Wondering who she was, I consulted Wikipedia and learned that she was the former Alva Vanderbilt–the same woman that Bertha Russell is based on in The Gilded Age.

From the chief of staff who publicly resigned due to President Woodrow Wilson’s ignoring of suffrage, to the well-timed telegram from a Tennessee senator’s mother urging him to vote yes on the Amendment, I was floored to find out that so many of the events of Suffs were in fact true. But more surprising was that I’d never heard the names of the women whose work impacted American history so significantly. The good news: the Broadway production of Suffs was filmed for PBS and the masses can watch—and learn about these women—if they missed the show.

Fosse/Verdon

In the late 90s, thanks to the revivals of Chicago and Cabaret on Broadway as well as the revue entitled Fosse, I became obsessed with choreographer and film/stage director Bob Fosse. I was transfixed by his dance style, and the specific movements of his dancers that characterized every one of his musicals and films. I spent a lot of time in the library in college, reading about Fosse’s failed ballet career due to his poor turnout, and how this dysfunction of his natural body led him to create an entirely new style of dance.

The revival of Fosse’s Chicago became such a huge Broadway hit that today, 28 years later, it’s still running. In the meantime, a movie adaptation starring Renée Zellweger, Catherine Zeta-Jones, and Richard Gere opened the musical up to new audiences. It’s important to note that the film bears little resemblance to the stage show in terms of its iconic choreography, but the story adaptation and songs are accurate to the musical.

The story of how Chicago became the musical we know is a fascinating one, and it came at a particularly interesting point in Fosse’s career. So much so that it’s a big plot point of the FX show Fosse/Verdon, a miniseries starring Sam Rockwell and Michelle Williams based on Sam Wasson’s biography, Fosse. I thought I knew so much about the choreographer’s work, but the miniseries enlightened me so much more. I learned that it was Gwen Verdon, the Tony Award-winning actress and dancer who was married to Bob Fosse for many years, who drove the Chicago project to Broadway in the 1970s. It was Verdon who consistently asked playwright Maurine Dallas Watkins for the rights to her 1926 drama of the same name, eventually convincing her to sell.

Watkins, reporter for the Chicago Tribune who had written about female murderers on trial as well as other “celebrity criminals,” turned the stories into a play called Chicago. Once Verdon secured the rights, the husband and wife team turned it into the iconic musical, along with composer/lyricist duo John Kander and Fred Ebb. I’d always known about the play, and even read it in college, but the miniseries brought my former research on the woman behind the man I idolized into focus. Without the persistence of Verdon, we might not have ever known this iconic piece of theater.

We often think of world building in the fictional sense. Game of Thrones, Gilmore Girls, Lord of the Rings, Severance have one thing in common: a distinct sense of place that is often almost entirely fictional. We can make sense of the plot points and characters within our understanding of that world. While documentaries about historical events are often informative and intriguing, historical fiction serves a different purpose. Makers of historical fiction build worlds out of facts about history blended with their own creative processes. Those worlds (even if they depict the very real New York City of 1883) allow viewers to discover a time, place, or person they might have no previous context for. Fictional characters become our friends, and we feel a natural urge to get to know them better and take a walk in their shoes. The journey of discovery through the eyes of characters we develop compassion for is an endlessly rewarding fandom experience. I’d love to hear your historical fiction faves in the comments!

Want more? Our Discord is where you’ll find tons of other fans chatting in our forums about the books, TV shows, movies, music, and games we all love! Don’t forget to follow us on Instagram, tumblr, and Spotify for more fandom content—and hit that subscribe button so you never miss a thing at rmrk*st!